Week 1:

University of South Carolina

June 10, 2014

This weekly blog I will be writing for the next nine weeks will cover my experiences working with Dr. Tufford at the University of South Carolina, Columbia. Dr. Tufford is interested in watershed ecology and water management, particularly the roles of wetlands in watershed ecosystems and potential effects of climate and climate change on land use and water resources. He works with policy makers and the public to incorporate ecological and environmental sciences into policy-related decision making.

The focus of our work will be characterizing dissolved organic matter (DOM) contents of coastal streams and looking at possible influences of land use on DOM variations. The project will involve taking water samples in the field, analyzing them in the biogeochemistry lab, and interpreting and explaining my data. Although I seldom give off ecstatic cries in exciting matters, I have to admit that I have been looking forward to this project for a long time, because it will be influential in my decisions concerning my future career and studies in water resource management.

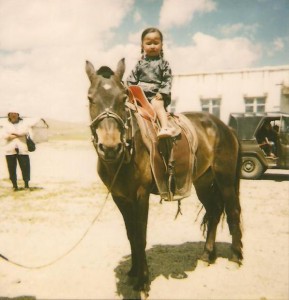

The color never returned. The only thing keeping the idea of living in South Carolina less alluring was the heat and humidity. On a hot May day in Mount Vernon when the temperatures got higher than during the previous days, a woman I met at Shepley’s (a store in Mt Vernon) said it is a joke compared to summer heat; after her subsequent remark on the fact that summer heat in Iowa is also a joke compared to the south, I made sure that I comprehended the gravity of the matter. Growing up in the extreme continental, dry climate in Mongolia, I remember feeling the immediate weight on my shoulders as I came to Iowa in late August my freshman year. Although I hoped that human adaptiveness will kick in fast, I knew that I would be a fish out of water in South Carolina; therefore, my first measure was to become a vegetarian, which is especially difficult for Mongolians whose main staple is meat. Second, I started amassing sunscreens on all the exposed areas of my body in order not to get tanned, which can happen in as much as 15 minutes. I remember my mom’s jesting comments, “Her color never returned,” as she points out that originally she gave birth to a fair-colored daughter, who she sent to Bayanhongor (Figure 1, 2) for summer months at the age of 3, after which she stayed brown for many years until now (Figure 3).

Iowa to South Carolina. On May 31st, I left Iowa with its gradual green rolling ridges and eminent blue skies that can potentially resemble Ghibli landscapes (Figure 4) at its prime.

Staying at Battuya’s in Chicago reminded of the extra factor I am having to account for when carving out my career plans: whether I will eventually return home or not influences what I can and can’t do.

Battuya is a doctoral student at the University of Illinois, researching cancer cells through flies; it is her 10th year here in the US, and returning home can’t be incorporated to her plans because there is null funding for specialized research like hers, and there isn’t a laboratory with facilities her research requires. If she works in the Academy of Sciences, she will not have a steady income, as most research projects are conducted in collaboration with foreign scientists. Prospects are similar for me and many other Mongolians, except probably those who are in more readily applicable fields like IT, economics, and engineering. Then why would people like Battuya want to go back to Mongolia? Although nearly any highly specialized person can find her/his niche in developed economies like here in the US, the sense of being “no one, a speck in the big crowd, or a cadre filling in the blanks to ensure the smooth workings of the economy” does not give the fulfillment it would if one were to work in Mongolia even by compromising his/her special interests like cancer cells in flies. In other words, marginal contribution of each of us is much higher thus more meaningful if we go back and work, though the heavy bureaucracy, poor institutional framework, and lack of understanding and need of specialized areas definitely create a dilemma we, young Mongolians, have to face. If Battuya goes to Mongolia to work, she by no means will carry on with her research; instead she will “probably work in international organizations on various projects” that don’t have anything to do with cancer cells in flies.

First week in Columbia. Columbia is a college town where University of South Carolina is located. Every morning, I walk from my apartment to my office, both of which are on the Greene Street; I pass through the horseshoe, the original complex from which the university campus expanded. It is Old Sem for Cornellians, though much bigger of course. The brick pathways, giant oak trees, little pockets of gardens with fountains, and the faint peach-colored buildings surrounding the central area provide great morning walks! Time takes a break here, allowing me to reflect, even in heat.

To my dismay, after all the hurdle in getting my driver’s license by April so that I am able to go on fieldwork for this project, I learned that I am not expected to be able to drive at all.

On the second day, Dr. Tufford, our lab technician, Warren, and I conferred about our plans for field work: we will be spending two days this coming week taking water samples. I had practiced stream flow measurement on a small creek nearby on my third day. Also, because this project was not layed out with my roles specified in detail, I realized it will be mainly dependent on what I want to know and how far I can go. Because at this point I don’t have enough background knowledge to hypothesize and ask various questions, I am a bit anxious. I very much appreciate that Dr. Tufford is instilling in me a sense of ownership in our project so that I can be actively involved in terms of designing the research. Most of the days, I have been on my own in my office learning GIS basics, occasionally helping Warren with cleaning viles and beakers, and performing tasks like creating a spreadsheet for stream measurement.

I hope in the following weeks my learning curve steeper.

Setsen is a geology major from Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia.