Week 5:

Science on the Rocks

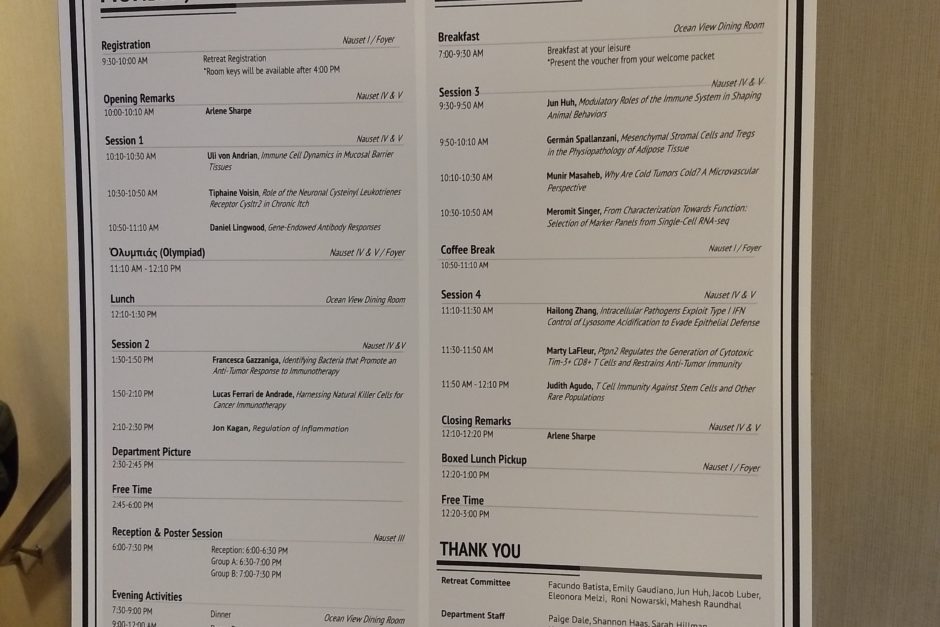

The Immunology Retreat schedule.

July 5, 2019

Life in the lab at the beach

This week, the Harvard Medical School Department of Immunology had its annual retreat. We stayed at the Sea Crest Beachside Hotel in Cape Cod. The Sea Crest is easily within the nicest three hotels I have ever had the pleasure of occupying. The food was excellent, the rooms were spacious and clean, and — yes — there was a beach.

The department bonded over the Immunology Olympics, which pitted a team of professors, a team of postdoctoral researchers, and a team of graduate students against each other. Some events were simple, like tug-o’-war. Another event was a relay race in which a team member had thirty seconds to suit up in BL2 protective gear, run to a table, and eject as many pipette tips into a goal as possible. The third event required every member to hold a pipette tip between their lips and pass a tube from teammate to teammate using only the pipette. Don’t try this in the lab, kids — mouth pipetting is a good way to be banned from lab work.

Aside from the Olympics at the retreat, department professors and postdocs presented their research in a series of twenty-minute lectures. As much as I love the work my lab does, it was interesting to see what else is making waves in the world of immunology. Our lab is mostly concerned with what is considered “basic” science. We seek to understand disease. Other labs focus on “applied” science. Some labs test drugs, vaccines, or other treatments for disease. Others develop software to compile and analyze the information gathered from basic science labs like ours. The presentations at this retreat helped me see how the cross-talk between these different approaches leads to scientific progress.

Margaret’s Biology Corner

Last week, I finished explaining the different disease models used in our lab. Starting this week, I’ll be explaining some of the information we gain from these models. These Biology Corners are more technical than my previous ones, but I will endeavor to keep them as simple as possible while still being informative. Each of these sections will end in a one-sentence TL;DR (too long; didn’t read) that names the technique I am describing and the big picture of why I use it. You’re welcome, Jack.

Whether you are a mouse or a human, all of your cells store their information as patterns in a molecule known as DNA. (Red blood cells are an interesting case. They are “born” with DNA, but lose it when they mature so they can carry more oxygen.) When the cell “reads” its DNA, it sends out instructions to other parts of the cell in molecules called RNA. When I harvest tissues from my mice, I save pieces of liver, spleen, and colon to freeze at -80 degrees Celsius. Because RNA is relatively unstable, keeping the tissues at such low temperatures helps prevent the RNA within from degrading.

After macerating each tissue sample, I can treat the homogenized samples with a series of chemicals that extract the RNA molecules from the cells. Next, I use a protein called reverse transcriptase to convert the information from my RNA molecules into DNA molecules. This serves two purposes: Firstly, DNA is more stable than RNA. Secondly, DNA can be used in a process titled “qPCR.”

My experience with qPCR predates this summer. In Craig Tepper’s Genetics class, I not only learned how to use qPCR — I used qPCR so many times that I lost count. Polymerase Chain Reaction, or PCR, is a tool that allows scientists to probe DNA to determine whether the patterns for certain genes are present within the sample. Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction, or qPCR, allows us to quantify how much of a pattern that we probe for is present within a sample. Since my DNA samples are actually modified RNA samples, qPCR can tell me how much the cells in the liver or spleen or colon are sending a particular RNA message. The RNA messages that I look for are used to create proteins. If I probe for DNA pattern x, I learn how much RNA x the cells were producing. The more RNA x produced, the more of protein x was being produced.

TL;DR: By performing RNA extraction, DNA reverse transcriptase, and qPCR on tissue samples, I can learn how much of a protein was being produced.

Margaret is a biochemistry and molecular biology major from Longmont, Colorado.