Week 4:

If You Give a Mouse Some Drugs

June 23, 2019

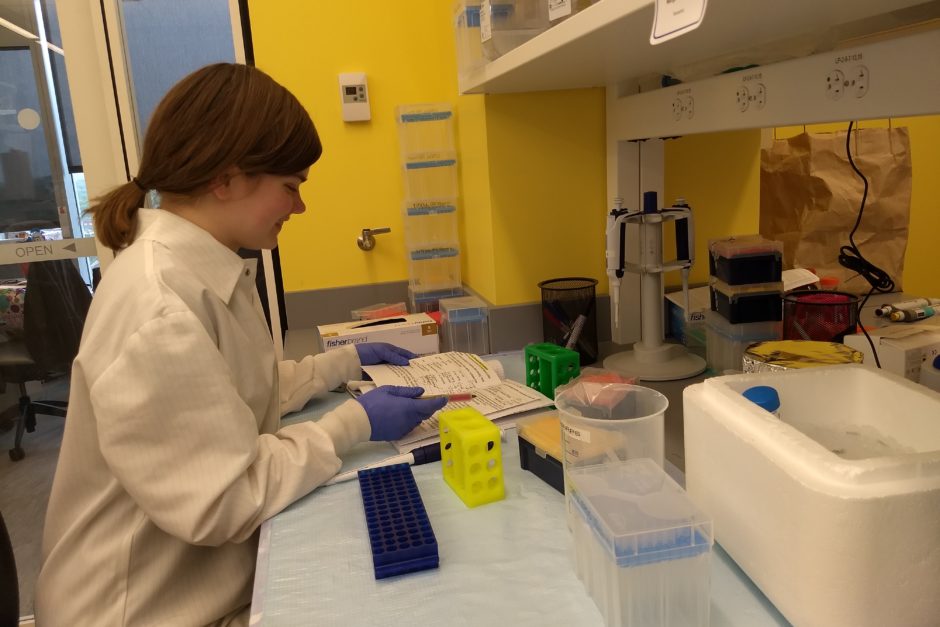

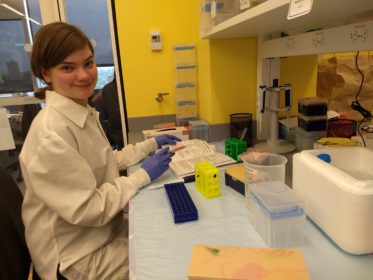

Life in the lab

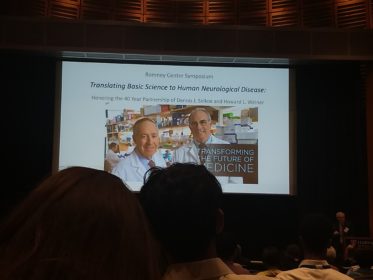

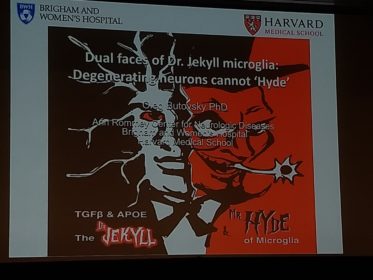

This weekend, our lab attended a symposium about neurodegenerative diseases. But Margaret, you might be thinking, your lab doesn’t seem to do anything related to the brain. And you would be right! Good observation. When Dr. Nowarski joined Harvard, he moved into the Ann Romney Center for Neurological Diseases for obscure bureaucratic reasons that I’m sure made sense to someone. Thus, a lab focused on the liver and large intestine found itself at a brain conference.

The co-directors of the Ann Romney center are Dr. Howard L. Weiner and Dr. David J. Selkoe. To celebrate their long history together, the symposium organizers invited scientists who have worked with the directors to present their research. Without the neurobiology elective I happened to take last year (thanks, Barbara), I wouldn’t have had a prayer of comprehending what was going on. As it was, I actually understood the research that was being presented by the world’s leading experts on Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and multiple sclerosis!

…Well, I understood most of it. Four-fifths, give or take.

Margaret’s Biology Corner

Last week, I explained how we can study the roles of cytokines by comparing how KO and non-mutant mice experience disease. I mentioned that autoimmunity researchers often “cheat” to give a mouse a disease. Today, I’ll explain what that means. You might learn why Jack Beaumaster describes my work as “harassing mice.”

The Nowarski lab studies ulcerative colitis (UC). Obviously, I can’t just give a mouse UC. UC develops spontaneously in humans for reasons still poorly understood. However, I can cause mice to experience symptoms similar to UC. These symptoms include weight loss, fever, inflamed intestinal lining, and bloody diarrhea (If you are unfortunate enough to be reading this while eating, my apologies). If a mouse is experiencing all these symptoms, it has what we call a UC-like phenotype. A UC-like phenotype is not actually UC, but it is close enough for our purposes. Indeed, that close enough is the autoimmunologist’s cheat.

So, how does one induce a UC-like phenotype in mice? Usually, drugs.

The most common UC model uses the drug dextran sodium sulfate, usually referred to as “DSS.” First, we dissolve the DSS in water. Next, we replace the mice’s drinking water with DSS-water. DSS damages the cells which line the large intestine. As a result, the large intestine becomes inflamed and leaks blood. Similarly to UC, the immune system becomes aggressively active at the intestinal lining. Ergo, DSS-treated mice develop a distinct UC-like phenotype.

(For those interested in learning more about DSS-colitis, an excellent review can be found here.)

Because administering DSS is so easy, DSS-colitis is the most popular drug-based colitis model. But there are others. Last summer, my project was validating the oxazolone-colitis (OC) model. To administer the OC model, I dissolved the drug oxazolone in ethanol. Next, I shaved the stomachs of our mice and rubbed the oxazolone on their skin. This primed the mice’s immune systems for future oxazolone treatment. Later, I used catheters to intrarectally administer oxazolone to the mice. This model produces an excellent UC-like phenotype, but it obviously involves more work than simply changing drinking water.

And that, folks, is how immunologists get around giving mice diseases whose causes are not fully understood. We give them something close enough. But we’re scientists, not sadists. We give mice diseases to enhance our understanding of those diseases to help humans, not just for kicks. Next week, I’ll talk about what we gain from these sick mice.

Margaret is a biochemistry and molecular biology major from Longmont, Colorado.