Week 7:

Meet and Greet

July 20, 2019

Life in the Lab

Allow me to introduce you to someone who is both friend and coworker to me: Dr. Kisha Sivanathan.

Kisha is originally from Malaysia, which is where she spent her undergrad years. She moved to Australia and earned her PhD at the University of Adelaide. She works in the Nowarski lab as a “postdoc” — a job title intimately familiar to anyone in academia. After a person earns a PhD, it is customary for them to spend time as a postdoctoral researcher. This is when they prove that they are an expert in the field in which they earned their PhD. They usually prove this by writing up papers as fast as Jack the night before a deadline.

In many ways, I have learned a lot from Kisha. Given her many years in research, she is experienced in a wide variety of techniques. “Are there any techniques you want to learn before you leave?” she asked me one day. “I want you to get the most out of this summer.” I asked to learn about flow cytometry, and Kisha grimaced. Flow cytometry, which analyzes cell populations based on molecular markers, is very popular in immunology research. Kisha is an expert in flow cytometry, but she finds the procedure tedious. Nevertheless, she agreed to teach me before I leave. A generous offer.

Never have I ever been to Australia nor Malaysia. I also have yet to work in scientific research outside of the United States. Kisha’s experience in these regards has really broadened my perspective. In her opinion, the biggest advantage of doing research in America is the time it takes to set up experiments. Because the big scientific suppliers are located in America, a reagent or piece of equipment might take two days to ship to a lab in the States but two weeks to ship to an Australian lab.

Margaret’s Biology Corner

Last time, I explained how we can find out what proteins a mouse’s cells are expressing through a series of protocols called RNA isolation, cDNA reverse transcription, and qPCR. This week, I’ll be talking to you all about a much simpler process.

As you will remember from my previous Biology Corner’s, our lab has been infecting mice with a bacterium named Klebsiella pneumoniae. This pathogen spreads throughout each mouse and causes system-wide inflammation. If we knew how much the bacteria replicated inside of the mouse and where it was replicating, we could measure the severity and spread of the disease.

Each mouse is injected with about 100 CFUs of K. pneumoniae. “CFU” stands for “colony-forming unit.” This means that when we spread the injection solution on an agar plate and incubate it overnight, 100 bacterial colonies will grow. These are easily observed as white dot-like clusters. CFUs are quantified through the advanced scientific technique of counting.

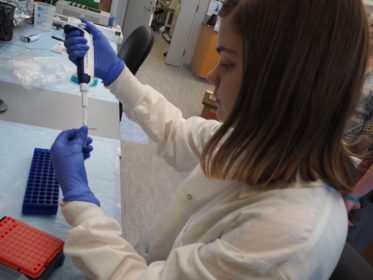

We can use the same principle for analyzing the severity and spread of bacterial infection. When mice are sacrificed, we collect samples of each mouse’s blood, liver, spleen, and colon. The blood is easy to work with. We mix the blood thoroughly to prevent clotting, then spread 40 microliters of blood on each agar plate and leave it to incubate. Unfortunately, the other tissues do not come in such a convenient liquid form. First, we weigh each tissue sample so that we can standardize the CFUs by milligram of tissue later. Next, we blend each organ into its own offal smoothie. I don’t recommend drinking it, but now our tissues are in convenient liquid form. We pipette the homogenate (i.e. smoothie) onto agar plates and let them incubate. By the next day, we can count how many bacterial colonies formed from each sample.

TL;DR: We can determine how much bacteria was in the blood, liver, spleen, and colon of each mouse by smearing blended-up organs on agar plates.

Margaret is a biochemistry and molecular biology major from Longmont, Colorado.