Week 2:

The Proverbial Office Water Cooler

How to get into Harvard: take the Red Line to Harvard Square.

June 5, 2019

Life in the lab

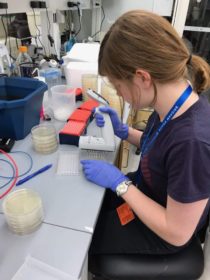

People are often drawn to the glamour of research. It has a reputation as an intellectually-stimulating line of work where your brain is always churning. And, to be sure, there is some of that. But research has its quiet moments as much as any other job. We label tubes, organize reagents, and take care of mice.

I enjoy the quiet work, too. Although learning new protocols and biological facts is exciting, the occasional break is necessary to ruminate over what I have learned. I simply pop in my headphones and wash equipment. Sometimes, the quiet work is a good chance to get to know my coworkers.

It is easy to get starstruck by your coworkers when you first start doing research. They seem like such smart, accomplished scientists and you — well, you’re just some undergrad. For me, it took a couple summers to sink in that all of my coworkers were “just some undergrad” five or ten years ago. Researchers are people, too, with lives and interests outside of their work. Last summer, I befriended a neighboring lab technician through our mutual love of tea. Thanks to my friendship with a certain other Cornell Fellow who is a Game of Thrones fan, I know enough about the show to keep up with my lab manager’s strong opinions on the final season. (Spoiler alert: He didn’t like it.) If you, dear reader, would like to try a research experience sometime, my advice is to not be too intimidated by your more experienced coworkers. Chances are you have interests in common with them that you may not expect.

Margaret’s Biology Corner

I promised to share a bit of the science behind how our lab studies disease. This week, I’ll tell you about what makes our lab’s mice so special. We have a colony of transgenic mice who have unusual genes written into their DNA. We mate these mice together. Offspring that inherit both unusual genes will have a different, normal gene removed. We can also control which cell types delete the gene. (If you want to learn more about this process, Jackson Laboratories has a very accessible write-up on the system we use.) Because our lab studies chemical messengers (“cytokines”), those are usually what we delete.

We know that cytokines carry messages between cells, usually cells of the immune system. The trouble is that we often don’t know what that message says. Furthermore, a given cytokine doesn’t always carry the same message. The effect that a cytokine has on its recipient depends on a number of factors, including:

- The location of the cells are in the body (Are they in the bone marrow? In the brain? In the gut?);

- The condition of the body (Is it healthy or sick?); and

- The identity of the cell receiving the message (Is it one of the many types of immune cells, one of the body’s many other cells, or even a microbe?).

When we breed a mouse to have a deleted cytokine, the cells of the mouse can no longer send that message. This mouse is called a “knockout” (or “KO”) for that cytokine. By comparing a KO mouse to a normal mouse, we can begin to understand the message within the deleted cytokine. Tune in next week to learn more about those comparisons!

Margaret is a biochemistry and molecular biology major from Longmont, Colorado.