Week 3:

Interviews and Literary Translation

January 20, 2016

Elizabeth Flick ’17, Arthur Vining Davis Fellow in Translation

And another week is gone! Things are definitely moving very quickly during this fellowship. My primary task this past week has been transcribing the first Spanish language interview I mentioned, regarding a woman involved in the Postville Raid in 2008. I have still not entirely finished it, but I have certainly developed a more than healthy respect for those who transcribe daily. It is a very meticulous and time-consuming task.

However, I can already see the benefits from listening to a recording of a native Spanish speaker for about eight hours a day. Last Tuesday we went to Schaller, a small town outside Storm Lake, Iowa. There, Dr. John McKerley, one of my site mentors and the lead historian and interviewer for ILHOP, and Mariana Ramirez, a native Spanish speaker and current history graduate student, led an interview with another Spanish-speaking immigrant laborer.

While I won’t go into details regarding specific content, the interview was generally fast-paced and very emotional at times. I went into the interview curious as to how well I would follow it; when two native speakers converse, in my experience they are generally much faster than when speaking to someone they know is a non-native speaker. I was somewhat surprised to realize I could readily follow the conversation and rarely encountered a word I was not familiar with, although there were several words or phrases that would have been new even as recently as a week ago. Clearly, transcription has done wonders for my understanding of the Mexican accent (at least of central Mexico) and vocabulary.

Of course, I still have plenty of room to grow, and while the further I go in transcribing the first interview the faster I am able to follow it, I am also beginning to encounter some of the issues I know will crop up when I start translating the interview (likely early next week). For instance, what is the best way to represent Spanish grammar errors or individual speech patterns in English? When a Spanish speaker uses “yo” to add emphasis (“yo” literally means “I,” but since the verb conjugation is different for first person than any other form, there is almost never any reason to use it other than emphasis), how can this best be captured in English (italics, a repeated phrase, something else entirely)?

John mentioned to me during the drive to Storm Lake (a four-to-five hour trip; I made it back to campus after midnight) that traditionally, oral history transcripts are seen as a type of first person literature. He was curious how literary translation differs from the more technical translation that has to be utilized when translating legal documents like the release forms I worked with a few weeks ago, as well as whether I agree with the idea of oral history translation as more literary, or view it as more technical. The question is actually extremely relevant; at this point, I think I will be taking a gap year before graduate school and most probably doing whatever work, whether as a volunteer, an intern, or a paid employee, in translation that I can in the intervening year to strengthen my skills. Generally, there is a much higher demand for technical translation and interpretation than for literary translation.

To me, oral history translation has to be seen as literary translation rather than technical translation, or at least as far more the former than the latter. Technical translation more or less assumes there is one “right” voice; think of the language you expect a legal document to have versus a warning sign versus a postcard. There are set conventions, a given voice or style of language that is the right one to use in each particular case.

However, in literature there is seldom just one voice or tone. They constantly fluctuate; everyone is capable of speaking more or less formally and writing that way as well. Part of the challenge of translation becomes finding the best way to represent changing tones and voices, both for one person or character as well as when multiple people are speaking. Most of the challenges I am currently anticipating in translating the interview lie in stylistic decisions of language; in technical translation, they would scarcely exist.

In short, technical translation can be a great aid in increasing vocabulary and learning to “hear” different tones and anticipate a given voice in a given area, but it is still very different from literary translation. During my gap year, I will need to take care that I do not lose sight of that reflection, and if I find myself mostly working on technical translation projects it would be very useful to keep myself in practice with a few side projects of a more literary nature.

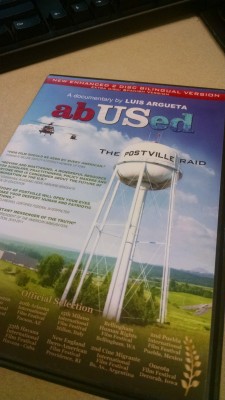

For now, I am simply letting my specific translation questions rattle around in the back of my mind; hopefully they will shake an answer loose before I actually require it. In the meantime, I am still also conducting side research into labor history, especially immigrant labor history. Jennifer Sherrer was kind enough to provide me with a documentary on the Postville Raid, which has proved immensely helpful in garnering insight into the conditions immigrants experienced prior to entering Iowa, during their time working at Agriprocessors, and a bit about their experiences since the raid. Some of the texts I am reading on the meatpacking industry reveal truly deplorable work conditions, often perpetuated when workers’ fear of deportation and simple need for any job they can find prevent speaking up for their rights.

Earlier I skimmed over the interview in Storm Lake itself, but I will return to it briefly now. Our interviewee spoke of her own experiences with harsh work and few if any breaks to relieve her hands, which during training they had been instructed to stop and do exercises for every fifteen minutes or so. She referenced a man she knows whose nerves in his hands and arms have become so badly damaged that he can scarcely move them, far less maintain a proper grip. While most recognize the dangers in labor industries in the 1920s and ’30s, and Upton Sinclair’s “The Jungle” brought to the public eye the horrific conditions in the meatpacking industry more than half a century after that, few seem to recognize the conditions people go through every day now, in a day and age when video cameras are on nearly every phone and people sometimes seem to sue at the drop of a hat. It’s sobering.

By next week’s report, I should have moved on to the actual translation process; it will be interesting to note how the dilemmas are worked out. There is the possibility that a few more interviews will be coming up which I may either observe or potentially conduct, but that could be the following week instead. In any case, the week ahead promises to be another busy one!

Elizabeth Flick is an English and creative writing major from Paris, Texas.